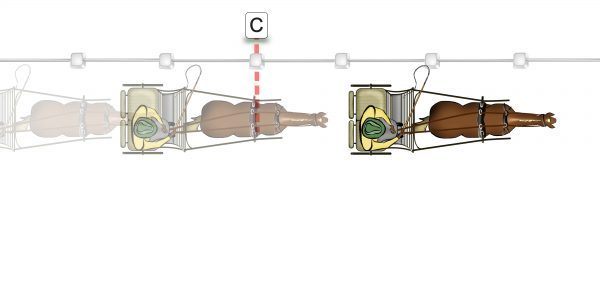

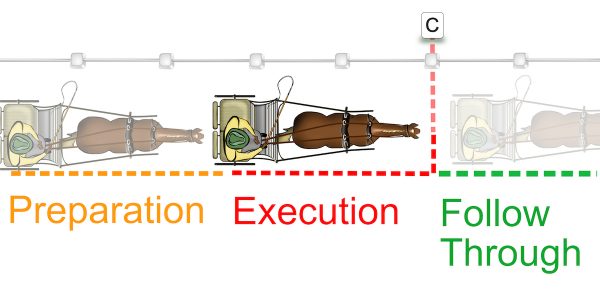

A transition should be viewed as a multi-phase event:

- Preparation

- Execution

- Follow-through

While each of these phases is important, perhaps the most important part of the transition is the preparation. Without proper preparation, the execution and follow through of the transition will be compromised. This can be revealed as either an abrupt transition, with the horse throwing the head in the air, or a long drawn out transition with little definition between movements.

The most common mistake that people make in approaching transitions is in their understanding of where a transition takes place. In carriage driving, the transition should occur at the nose of the first horse in the turnout. So if a single horse is asked for a transition to walk at C, his first walk step should take place as his nose crosses in front of C. For tandems and four-in-hands, the transition occurs at the nose of the leaders.

But the definition of where and when a transition should happen (place & pace) has further implications than accuracy on a dressage test. It effects the communications between the horse and driver. Without a specified goal of when a transition should happen, the phases of the transition often run together.

No Definition of Place

No Definition of Place

When the equestrian puts no objective goal for where a transition is to happen, the transition often becomes drawn out and disorganized. If the transition is between gaits, there is often little correlation between one gait and the next. Perhaps the horse has a very nice, steady, rhythmic working trot, but the walk following the transition is sluggish, lacking the engagement and energy that the trot exhibited. If the transition is within a gait, the transition may never be apparent. For example, a working trot to a collected trot transition may simply look like degradation of the trot from a working trot to trotting slowly.

Choosing a place where a transition will be complete allows the equestrian to evaluate how long the horse needs to make the transition, and the quality of the movement both before and after, the transition. Of course, that can lead to another common pitfall in transitions.

A Rigid Definition of Place

When faced with a directive such as “Walk at C,” many riders interpret that the transition happens “at C.” Following that line of thinking, they wait until the horse is at C to ask for the transition. That ignores the fact that it takes time for a horse to prepare for and execute a transition. During that time the horse is still covering ground. If the horse is trotting at about 13 kph, he’s covering about 3.5 meters in one second (that’s just under 11 ½ feet for those of you who don’t think in meters). So if it takes the horse one second to prepare for a trot to walk transition, and another second to make it happen, the horse will need over 20 feet to make the transition happen for you!

If the driver waits until C to ask for the transition, it wouldn’t be complete until just before the quarter line. If a rider waits that long, the transition would happen in the corner of the arena. This often leads to the equestrian throwing on the emergency brake as they sail past the mark, which leads to an abrupt, unbalanced transition. That unbalance is transferred into the gait that follows the transition. The result is that after the transition the equestrian has to spend time and energy helping the horse re-balance in the new gait instead of focusing on the next movement.

Rather looking at C as where the transition happens, the equestrian should view C as where the transition is completed. This allows your thinking to consider where the preparation for the transition must be made, in order to complete the transition at the mark.

The most useful tool for preparing for a transition is a half halt. Half halts aren’t just for halting. Half halts prepare a horse for an upcoming movement, regardless if that’s a change in gait upward or downward, or a change in direction. Having a good clear half halt established allows you to inform your horse of an impending change in movement.

A Half Halt has to be built from the ground up.

Take the time to work with your horse methodically through a lesson plan that is just about building the half halt. Setting out to define the half halt as the only goal for a training session allows you deconstruct every aspect of the half halt, and put it together as an effective tool for training. (see my Half Halt Page for more info)

Once the half halt has been agreed upon by both the horse and equestrian, it can be put to use in just about every other aspect of their training. For transitions, the half halt should be the first thing you do to prepare your horse for the transition (preparation.) Then it should be followed by a release and the subsequent request for the transition (execution.) Finally, you should be focused ahead allowing the horse to move freely through the transition (follow-through.)

Just as with the half halt, when it’s time to work on transitions, you should focus a workout solely on transitions. Set out specific marks to make your transitions, and evaluate how well your timing is going for the three phases of each transition are working together. Test, observe and test again until your transitions are smooth.

Specific work on transitions will mean that you’ll get your horse right into his best walk, trot, or canter the moment that you ask for it, rather than a dozen strides later. That will give you the flexibility to focus on the next movement you should be focused on. After all, great gaits don’t necessarily create great transitions, but Great Transitions will always enhance all of your horse’s gaits.